If you’re looking for a book about what it means being home, leaving home, waiting to return to home, and knowing both you and home won’t be the same when you get back, this is the book for you. Bottomlands by Madeline Trosclair-Rotolo shows her reader “an inevitable washing/away where only so much can stay behind to bear witness” (13). This collection of poems shows their reader how much place can mean to a person and how the nature of where we live can encroach on who we become.

Madeline Trosclair-Rotolo’s Bottomlands gives us a speaker that becomes tropical storm. The speaker of the poems speaks to the reader by saying: “I am an endless stream//of hot gulf air awaiting a name” (15). The reader will see that the speaker of the poems matches the emotions and destruction of the environment they call home. The essence of hurricane season becomes a part of the speaker’s nature. We see our speaker, at times, aspire to be capable of the level of destruction they’ve seen the storms hold. They often look up to the power of the natural disasters they have witnessed. But this poem of collections is not one built on fearing and running away, it is structured in a way in which we see the speaker’s want to reclaim the strength of the storms they have seen take from them, time after time.

Poems like “Lament for the River’s Loss”, use repetition to hold onto the memory of things physically and emotionally washed away by storms of the past. The speaker understands themself through the traditions and rituals of storm preparations, shown in the poem: “Get Your Generators Here”. There are poems that show the conditioning and second nature for survival created by the always daunting truth that a storm is on the horizon. The culture of the speaker’s homeland has created a unique common sense in those who also reside there. The culture for survival embedded in the speaker is also how the speaker grows to understand the world around them.

In Bottomlands, the speaker is compared to a storm by family members. They associate themselves and their path through life like a storm. In “Lament for the River’s Loss”, the speaker says: “I remember my mother telling me I make category fives out of 3pm storms” (17). A later poem, “Geographies”, tells us “It is easy to be dwarfed as a child, easy to be made small/when a category fives has a width of 3oo miles.” (20). The speaker defines themself through comparison to the storm.

This collection hints at the permanence of objects and people in areas that get targeted by storms. We know what is happening to them through the progression of the storms. The world created on the page also mirrors and foreshadows the actions being taken to help prevent or alleviate damages to the land from future destruction caused by erosion and predicted storm patterns. In “We Drowned the Oysters this Year”, the lines “Rocking chairs etch their names into wooden/floorboards with each passing quake”, shows that through all the abrupt changes made to the land, there is a way to gradually leave a mark. A trace or proof that those living there existed and will remain, even if it takes them time to return.

There is a lot of mention of stillness and moving in the poems to emulate the way water and land functions before, during, and after a storm. The poems show how both the inhabitants and the inanimate objects, like water itself, function. We are told: “everyone stood and watched cities fishbowl” (14). We are told: “Sometimes we have to give ourselves over/to what the body softly chases” (31). We are told: “We drink in the rain together,/and talk about future plans” (35). We are also told: “Tombstones/ resurface, mouths agape and lopsided gasping/for a breath of muggy air” (41). Trosclair-Rotolo spares no part of the storm process and aftermath from these pages. They create a world so full of all the details of what gets affected by hurricane season, from the oysters to the alligators, to the overflowing sinks, to the highways and maps of grief.

An Interview with Gabrielle Côté

Gabrielle Côté has been featured in two previous Beaver Magazine issues and is now also our header artist! Our editor, Haley Winans, conducted this interview.

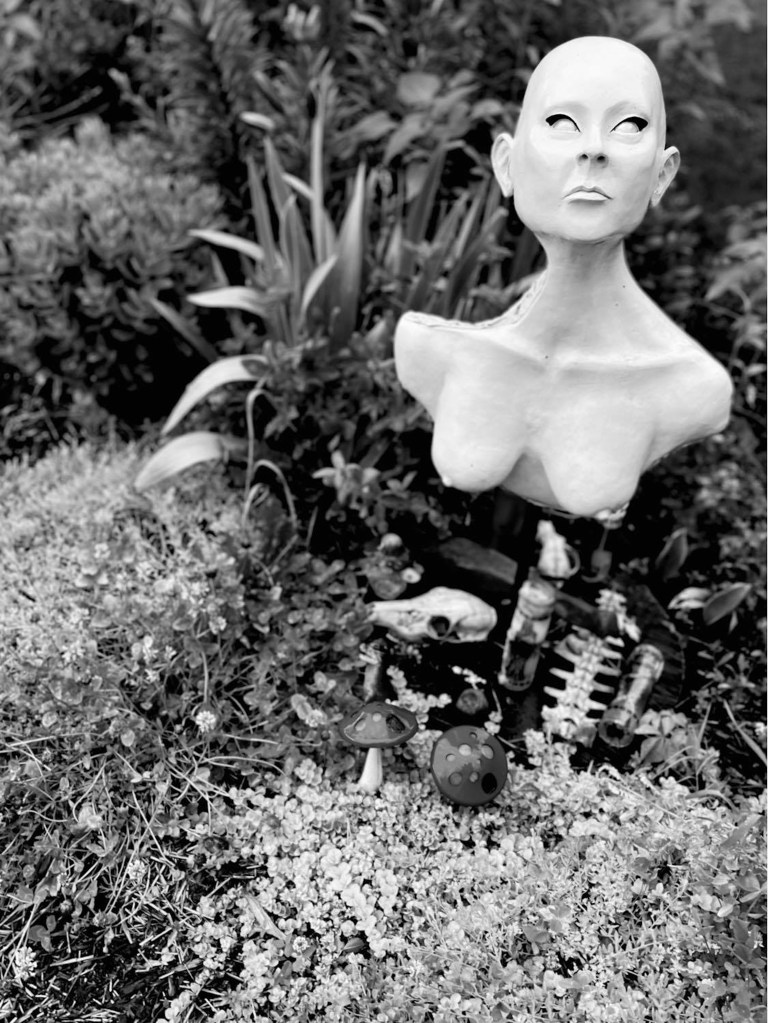

Hey Gabbi, it’s so good to speak to you through the interweb echoes, my gorgeous angel bean! Please tell us beavers slowly crowding around you about your recent art obsessions. What drives your process?

I’m so excited to get into it! Thank you for being interested.

In regard to what drives me to actually document things is that I’m scared of losing moments or forgetting experiences in old age or getting rid of physical things that hold memories. I once heard that “the artist is the ultimate collector”. If I can find a validating excuse for saving things like my dog’s puppy teeth, hair from my previous haircuts, and things like receipts or old buttons, I’ll reference that quote each and every time. I think it was a previous professor who said that to me but I’m not certain.

The artists I find inspiring right now are primarily abstract expressionists and mainly those from the 70’s. In regard to application philosophy, I really love Richard Deibenkorn for the past year or so. He considers a 90 degree visual plane in his Ocean Park series which I find progressive in that it’s globally sort of a measurable approach. When I graduated high school I moved to Los Angeles and worked in a café right around where he had his studio in Ocean Park. I highlight him primarily because his expertise ranging from his early observational work into his expressionist work is consistently experimental and yet still appears deeply concentrated. His work is dear to my heart, and one of the first breakthroughs I had with understanding abstract expressionism the way that I do, and through his process I discovered a newfound trust in my own process. Also, he doesn’t like to use erasers and I don’t either.

Anders Nilsen is an illustrator that I stumbled upon in a public library. His graphic novel Poetry is Useless was one of the first times I saw a fine ink application and journal-type documentation that I could relate to. It’s a hardcover book of non-linear scans of his sketchbook entries. I was inspired and not discouraged, and it made me feel challenged in a good way. His perspective on the contemporary world touches a lot on the advancement of our political, economical and technological society. There’s definitely a dark undertone of topics being balanced with the whimsical style he’s adopted.

Pat Perry is one of the most incredible artists walking the earth right now, the work speaks for itself.

What drives me as a creator is generally a fear of losing an idea or a moment and it getting lost in the back of my brain and it becoming unretrievable or altered over time so I try to keep notes. What I get interested in, I do deep dives into, and take tons of notes. At that point, it’s like, I either write a Gabrielle encyclopedia of what would ultimately end up being biased opinions and interests which no one would care to read until assumingely posthumously- or, I take that information and put it into developing myself as a visual artist, which is what I’m most confident in, but I do love playing with writing often in my process.

I think the real key is to be proud of being a curious person. Oh, and also nurturing the relationship that exists between my inspirations and imagination and the I that exists within and outside of them. Things that get us excited should be honored for the sake of whatever that thing is and I believe it’s vital to be grateful that you two have met.

Yumi Sakugawa has really good philosophies in regard to the relationship between art and the artist that I recommend anyone reading this to consider.

What’s your relationship with color on the page?

I use alcohol-based (Copic) markers when I color hand-drawn illustrations, and my favorite part about them is their ability to layer really well, because alcohol evaporates and the pigment will stay, so it can be extremely versatile. When working in more expressive ways, like with gouache and mixed media, I consider the form in which the material would benefit taking a new shape into. I have a pretty limited color palette. I’m most at peace while working with neutrals but I’m aware that heavy saturation can catch the eyes of passersby in different contexts, so I try to use that to my advantage depending on the project I’m working on. Each of those approaches are a result of/require different head spaces for me.

Your work seems to let the mundane like skateboarding or gardening, dip and often dive into the surreal. Can you tell us more about this relationship?

Growing up, until about 18, I was around skateboarding culture a lot. I really loved the style of deck graphics and the idea of street art and slap stickers, and I realized at an early age that you can always start where you are with what you have. Skateboard culture graphics and styles were my original inspiration. Infinite Rot specifically, which no longer exists.

I have to give big thanks to that period of my life because it is a valid part of my style evolution. The way that I depict mundanity is just a stylized approach. It’s more fun for me and I can’t communicate in any other way that feels right to me. Making normal things in the world a little synthesized with other sorts of dimensions feels natural and keeps me engaged.

Ok ok ok tell us about your love of comics. You made me my snail girl comic and I stare at it every day in awe. Which ones are you reading? What comics are your big influences? What is the beauty of comics to you?

Growing up I was never allowed to read comics and still to this day I’m not sure what’s really

going on in the big, popular world of comics. I really began just journaling and combining little images with silly little text entries in my sketchbooks in about 2014. I had some friends and family that I shared them with who all really loved them and urged me to pursue it. I started realizing graphic novels were a thing in about 2017 and I also took a few classes at MICA beginning in 2019 that lent me the opportunity to experiment and learn a lot about text/image relationship and did a lot of trial and error. It’s really fun for me to consider all of the possibilities.

I really get excited about how many variations of a story can be told depending on the visual

choices made by the artist. You can have one story plot in mind, but a million application possibilities that will influence the story. You can stick everything into a recurring box structure with quote bubbles, or you can separate text and image, you can hand letter your text, you can scan in photographs and combine with type. There’s so many options. Ultimately, the story changes based on the artist’s choices and it’s up to the artist to make the choices that best support the mood and message they’re trying to express and the relationship they want to have with the reader. I’m so glad you love the snail comic. It’s based on a Chinese folktale!

My most influential comics are Marc Bell, Emil Ferris, Jim Woodring, Anders Nilsen, and Roz

Chast.

What projects/ideas/dreams do you have in the works?

I really want to work in 3D again. Right now, in my program at MICA, it’s heavily 2D and

formula-driven. I miss working in 3D a whole lot. Once I attain the space to work efficiently in that realm, I’ll work on lots of things I’ve been incessantly daydreaming about. I’m looking

forward to larger-scale paintings and sculpture. Plaster is my absolute favorite! Sculpture studio is my happiest home. In regard to 2D, right now I’m super into background design and hand-lettering. Trying to stray from digital stuff for the time being. I’m looking forward to the tail end of my illustration degree and continuing to work with the Baltimore Banner and other editorial publications!

What does your creative process look like? Iced coffee, Elliot smith, meat puppets, your pets? How do you follow a creative idea?

Elliot Smith’s birthday was just yesterday as I type this! Realizing we’re both Leo’s. Yes I love all of those things! Pets can be distracting though. I try to listen to full records when I work which can be challenging. I find I get less distracted when there’s a bit of air to breathe in the music I listen to if that makes sense. I’ve tried to listen to podcasts or watch shows when I can’t find the right music, which some people can do, but it’s not my thing. I like things that feel kind and quiet primarily, and I work quite well with certain types of synthetic music as well.

I’m most efficient when I wake up early and go immediately into drawing, otherwise I get easily consumed with junk on my phone or the outside world. I spend a lot of time in public libraries and I live next door to a used book store which helps me in sparking new interests. When I go to the library or get new books, I take heavy notes on them in my sketchbook. Anything I hear that inspires me or catches my interest I write it down, and it’s always good to reference them from time to time. I have about 60 sketchbooks from the last 5 or so years, and I’d say roughly 50% of their contents are written text or artist references.

Recently, I’ve been trying to remind myself that it’s not necessary for me to respond to my

immediate world. For example, I don’t need to feel obligated to find inspiration in yesterday or last month or tomorrow, rather I’m trying to give myself permission to consider 10 years ago, or 10 years in the future. Those things sort of yield the most freedom and imagination potential. It also takes a lot of pressure off to not try to articulate what’s happening right now, but try to use past experiences or future possibilities. I think that’s my biggest thing right now.

Thank you for having me!

Here’s a link to my Spotify playlists that I’ve worked alongside over the years.

Gabrielle Côté is an illustrator and designer living and working in Baltimore, MD, pursuing an Master of the Arts in Teaching (MAT) degree and a BFA in Illustration. Their illustration work synthesizes imaginative characters with the observed modern world. Advocating for the strength deriving from the process of simplification, Gabrielle’s work offers an invitation for the viewer to create trusting relationships with characters, repeating original symbols, and new worlds. You can explore more of their work at http://www.gabriellecotenielsen.com or @byegabthanks on Instagram.

Prompt Series Announcement!

Hello Lovely Beaver Babes,

We have a fun new regular feature coming to the blog we can’t wait to share with you. Every month, the Beav team will be coming up with a new set of prompts for your creative enjoyment! These prompts will be posted on our blog and social media accounts.

If you happen to connect with and respond to one, we’d love to see what you come up with. On our submittable, we have a new prompt response category if you’d like to be published in this new blog series! We’ll consider responses in any genre of any length.

Submissions in this new category will receive an quick response, likely under a week. We’re so excited to see what you come up with, have fun with these first three prompts!

Image Description:

Beaver Mag Blog Prompts

- Write an obituary for your dead self/ something you overcame

- Write a nocturne that becomes an aubade with a drizzle of elegy

- Make a piece of art that encapsulates a weird ass dream of yours

2023 Best of the Net Nominations

Hello Beaver Friends!

We hope your summer hasn’t been too sticky and sweltering so far. It was no easy task narrowing down our nominees & we’re so endlessly grateful to everyone who’s helped making Beaver Magazine’s second year bigger & better than we ever could’ve imagined. We cannot wait to see what year three will bring & can’t wait to see how big this beaver family grows. Now… what you’ve been waiting for….. our list of nominations by genre!

Poetry

Fiction

Creative Nonfiction

Artwork

Wishing you gentle sunshine and sweet times,

Ellery & Haley

DAM, NOW THAT’S WHAT I CALL CRAFT!: Beaver Mag Talks Poetry w/ Jose Hernandez Diaz

Interview & Article by J Clark Hubbard, Interview Editor

The Poet—Jose Hernandez Diaz—is sitting at one of those off-white circular picnic tables that haunt every American convention center. He’s the only AWP attendee in the break area who isn’t on a phone, reading, or writing. The tables around him are piled w/ promotional flyers, unwanted magazines, forgotten chapbooks, & coupons for every cuisine Seattle has to offer (see also: all of them) while the thousands of writers, editors, students, & other attendees are packing the air of the warehouse-esque convention center w/ conversation. His ability to find some semblance of calm amongst the chaos reminded me of his prose poems, many of which seek for a simple truth in a complex tapestry.

Diaz’ writing is unmistakable, recalling the works of James Tate, Frank O’Hara, & MF Doom. Re: Doom, Diaz says he’s always appreciated “the non-sequiturs in his work, the casual cadence, the everyday imagery,” markers that O’Hara & Tate often exemplify in their poems. Diaz’ pieces—esp. his prose poems—are wild, wandering meditations on humanity/earth, typically preferring colloquial language rather than the academic prose that tends to turn off the average poetry reader. For Diaz, these incredible landscapes & universes happen “in the initial burst, w/ the line that inspires it—the first line or the title.” Off the cuff, he estimates that 75% of his poems are done during the drafting process, while “editing is making it smoother, maybe adding transitions, & incorporating some more specific imagery.”

Diaz plays w/ repetitive language & structures in his work, esp. present in his prose poems. “It’s an organic, intuitive process” says Diaz, “it’s not necessarily mapped out or scientific.” Not for the last time, our conversation turned to music to better understand the art/process of poetry. “In music you need to have rhythm, strong imagery, & repetition” says Diaz. “Repetition can sorta lull the reader in, but also surprise them—a mixture of surprise & familiarity works well, sometimes you can be subtle, sometimes more striking & surreal.” These ideas are represented well in “Goblin with Hummingbird Mask,” which we had the pleasure to publish in an earlier issue of Beaver Magazine.

Even if you’ve never read a Diaz piece, you’ve undoubtedly bumped into him or his work on social media. He’s one of the more prolific poets of Twitter, partially due to the variety of workshops he leads. (Like any good teacher, he completes the assignments alongside his students, leading to an enviable output.) My biggest question coming into the conversation was simply: How? How can one person teach, write, read, & publish so much & still feel alive? Diaz has the answer, but it’s not one that either of us are particularly happy about. “Even on the weekends…” Diaz pauses, grinning & sighing before the big reveal: “I go to the library.”

Most artists (I didn’t want to commit to all artists, although I’m pretty sure that’s right) must sacrifice something to create—sleep, health, money, relationships, etc. “It’s always greener on the other side” says Diaz, “when you’re single you wanna be in a relationship, when you’re in a relationship you wish you had more time for writing, more freedom.” Every artist thrives in different circumstances at different points in their lives, but each artist is ultimately responsible for finding the right balance that allows them to live & create. “I don’t go out a lot in terms of partying,” says Diaz. “I did that a lot when I was younger. In high school, college I was partying all the time. I feel like I got it out of my system to the point where now I’m pretty focused.” Thus the weekend worship at his local library, the constant stream of workshops, & the terrifying productivity that’s made Jose Hernandez Diaz one of Poetry Twitter’s must-follows.

Outside of the connections one can make on socials, Diaz considers Twitter a sort of “second family,” one where he can be his “Poet Self.” Thanks to the stereotypical macho culture Diaz grew up in, he has often felt a divide between himself & family members: “My cousins & I are cool, we watch boxing & things like that, but you don’t really talk about poetry in a working-class type of environment in Southeast LA.” But on Twitter, Diaz knows that his art & his efforts won’t go unnoticed. Considering his everyday life, Diaz says “If I’m in The Southern Review? Who cares, the first question I always get is ‘how much does it pay?’ They don’t understand what it means, the prestige, or anything like that. That’s when I go to Twitter. It allows me to live in two worlds at once.”

Although AWP only allowed us 10 minutes of conversation—his panel on The Joy of Surprise in Generative Workshops was starting soon—we ended our conversation discussing MF Doom’s discography & making plans for our next conversation. As he walked away, I heard one line echoing from our earlier conversation on the prose of O’Hara & Tate—”I’ve always liked the casual writer.” Considering Diaz’ manuscripts, publishing record, & smorgasbord of workshops/lectures, I don’t think anyone would call him a “casual writer,” but for Diaz, it’s more of an aesthetic: “the appearance of the casual writer.”

The late Charles Simic zeroed in on this idea in a 2010 piece titled “Essay on the Prose Poem,” available thanks to Plume Poetry. Simic writes: “All poets do magic tricks. In prose poetry, pulling rabbits out of a hat is one of the primary impulses. This has to be done with spontaneity and nonchalance, concealing art and giving the impression that one writes without effort and almost without thinking − what Castiglione in his sixteenth-century Book of the Courtier called sprezzatura.” In the same way that a grumpy museum-goer might mutter about how the works of Janet Sobel or Barnett Newman are overly simple & childish, the prose poems of Diaz & Simic offer the world a clean, deceptively easy-to-grasp surface, containing complex multitudes that whisper secrets of the great beyond—but only if the audience spends time w/ the piece & is willing to wrestle w/ the art. It’s no coincidence that Diaz teaches this Simic essay in his workshops, encouraging younger artists to find their voice & aesthetic, esp. when the world deems a piece of writing “too casual” or “too easy.”

Jose Hernandez Diaz was born in Anaheim, CA (1984). He is a 2017 NEA Poetry Fellow. He is the author of a collection of prose poems: The Fire Eater (Texas Review Press, 2020). His work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Boulevard, Cincinnati Review, Colorado Review, Georgia Review, Huizache, Iowa Review, The Nation, Poetry, POETS.org, The Southern Review, Yale Review, and in The Best American Nonrequired Reading. He has been a finalist for The Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, The Colorado Prize, The Akron Prize, The Journal/Wheeler Prize, The Wisconsin Series, and The National Poetry Series. Additionally, he teaches creative writing for various organizations, including Beyond Baroque, Litro Magazine, The Writer’s Center, and elsewhere. Keep an eye out for Diaz’ first two full-length collections: Bad Mexican, Bad American will be published by Acre Books in 2024, & The Parachutist will be published by Sundress Publications in 2025.

A Review by Terin Weinberg

What We Remember, What We Name, and How We Carry It With Us

Nomenclatures of Invisibility by Mahtem Shiferraw is a call back to the self, to ties to ancestors, the land that nurtures, and acts of displacement that disrupt those bonds. Shiferraw’s distinctive narrative style carries the reader across 81 pages of poetry. This is a book for those who want to divulge into the unraveling mystery of defining the self and home through inheritance of memory, names, nature, ancestors, and paths taken or almost taken.

Shiferraw’s first poem, “Eucalyptus Tree I” and a later poem “The Eucalyptus Tree II” tell of a tree that calls the narrator “child” and “daughter”. Nature is used as a powerful symbol for naming and relationship definition in the collection. The strength of naming and trees are present throughout the poems, which is seen in a later poem, “For Micah, My Neverborn”, in which the speaker calls an unborn child’s growth and cessation of growth reminiscent of a tree. Shiferraw writes, “I drank so much water// thinking this body to be a tree, thinking I could summon/it into nurturing you, slowly, slowly” (15). The poems work to mirror the body and the progression and permanence of the natural world. Shifferaw continues this notion in “For Micah, My Neverborn”, through “believing this seed would need to survive/the spices of my ancestors to grow strong” (15). “Mother Mango II” also shows how human it is to embody the resilience of something as familiar as a tree. These poems bare down on how the body and the rest of the human experience aren’t so different from the workings of a tree in the soil. How they are as intricate as lineage and culture.

Nomenclatures of Invisibility shows the direct link between past, present, and future and how they interact closely to create the reality of this collection of poems. The link is not only necessary to support the truth in the poems, but to show how generational trauma is being carried in the speaker’s body. Shiferraw writes of a miscarriage: “I don’t know how to do this, how to continue/carrying with me a body riddled with new wars.//I don’t know how to bear the wars of other women—/mothers, grandmothers, aunts, sisters—our language//is that of dying. I had so much to tell you, so much…” (16). The poem’s speaker carries around personal and ancestorial trauma in their own body and owns the memory of their ancestors and their battles faced. “The Breaking” shows this carried trauma through a direct lens by stating, “I was born/with grief already etched/deep into these irises…” (37). This collection contains multitudes of richly linked familial identities and realities throughout.

The identity of the grief and trauma present in the collection is defined carefully through historical poems like “Wucalle”, which allow the reader to see the wounds of the past and why they are ever so present. Shifferaw writes to the reader: “…here, I expect you/to go out into the world, and reclaim my/narrative” (24). “Dust and Bones” states: “This is not my story;/but in it I stand/called by other names; the ghosts of my past selves/all reaching at the same time/and all refusing this—” (34). Nomenclatures of Invisibility is not just a map of grief, but a new claim on the ownership of Ethiopian history and what it means to own one’s own story.

The speaker in “Transcendence” shows how the grief and trauma attached to these poems is not all of sorrows, but of strength— “…here is my name: I am more, I am free” (53). This collection is not only of loss, but of pride in the culture carried in the bones of each poem, of each speaker on the page. These poems show how we are not only our present self, and how “we walk/in unison too: our backs bending at once…” with our ancestors (13). Shifferaw truly showcases how powerful ties to the past can be, and how the stories we hold tie us to home, however we choose to hold onto and define those spaces.

An Interview with Michael Montlack

Questions by Shallom Johnson, Art Editor

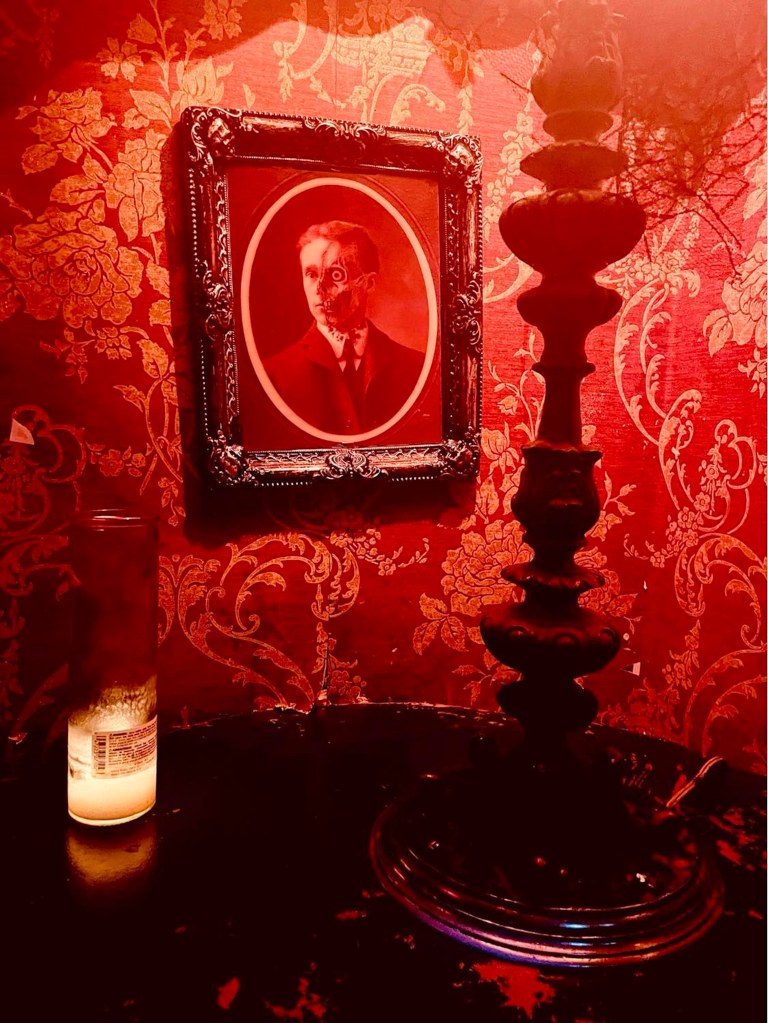

This collection of photographs seems to take me on a journey; it feels like a series of postcards from a long and winding road. Is there a common thread that runs through these images, for you?

Funny you say that. During the pandemic summers, I drove across country. Most of these photos were shot on the road. Avante Garden in Kansas, outside Lawrence. Electric Nebraska taken from the train. The Merman in upstate New York. Easy Landing in NYC at Night of a Thousand Stevies, a night devoted to Stevie Nicks. The thread is my impulse to travel and find strange beauty.

Who are your biggest artistic influences?

I’m mainly a poet. Many of my poems are portraits. Like photographs. My influences include writers like Elizabeth Bishop, Gertrude Stein and Dorianne Laux. Alice in Wonderland too. And musicians like Stevie Nicks and Natalie Merchant. I am drawn to artists who use whimsy and peculiarity: Botticelli, Dali, Gaudi … And comedians: Jessica Kirson, Amy Sedaris, Yamaneika Saunders.

Which subject matter are you most drawn to capturing, and why?

Queerness. Whatever that means. As a queer person, I love finding beauty and humanity in what’s considered strange.

I agree with photographer Duane Michals who said, “I wish we realized that we are queer creatures. It’s a queer life. The universe is queer. It’s bizarre and queer.”

What kind of camera do you shoot with?

I use my iPhone. I used to shoot black and white on a 35mm. But my phone is more convenient. And it lets me be spontaneous and adventurous.

You are well-known for your work as a writer, editor, and educator. How do these photos relate to your writing practice?

I wouldn’t say well-known but thanks. When I write and take photos, I channel my father, who was a mechanic and carpenter. I spent many afternoons working with him in the workshop. Helping him build, sand, and stain. He taught me to roll up my sleeves and get into it. To make something strong. Anything less is wasting your time, he’d say. I want to have my feet on the ground when I make art. I want to be authentic, earthy and welcoming, rather than formal and fussy.

Any plans to combine these two mediums in the future?

I have a photograph I’m saving for the cover of a book of poems I am completing. If the publisher goes for it. I’ve met artists at artist colonies, who have proposed collaborations, their imagery, my words. I’m open to that. Some have given me artwork for my book covers. Once I named paintings in a series by Deb Mell. That was really fun.

How would you describe your overall aesthetic as a photographer?

Earthy Etherealism.

What are you looking forward to for the rest of 2023?

Travel. Seeing my friends across the US. Completing my next book of poems. And editing a young adult novel I’ve been working on. I’ve discovered camping at gay campgrounds. Can’t wait to do that more.

Anything we haven’t asked about that you’d like to mention?

Thanks for including me.

Michael Montlack is author of two poetry collections, most recently Daddy (NYQ Books), and editor of the Lambda Finalist essay anthology My Diva (University of Wisconsin Press). His photos have been featured in Salt Hill, phoebe, Northwest Review, the “Just Say Gay” issue of SoFloPoJo and (on the cover of) Gertrude. His poems recently appeared in Prairie Schooner, North American Review, december, The Offing, Cincinnati Review, and Poet Lore. He lives in NYC.

An Interview with Margaret Hart Lewis

Conducted by Art Editor, Shallom Johnson

Thank you for taking the time to give our readers a window into your work! Can you walk us through the process of creating one of your artworks?

I usually see the piece in my mind’s eye before I begin work on it. I contemplate the visual and allow the details to unfold. When I feel the clarity of the vision, I begin the work. Most often, I paint first and then create the woolhooking portion of the piece.

Once the painting is completed, I take it into my wool hooking studio and begin selecting yarn and wool strips to complement the palette of the painting. Then I sketch a design for the piece and once I am pleased with the design, I hook the piece. It is fun to watch it all come together! Finally, I put the painting and wool piece together in a frame and hang it on the wall of my studio to study and enjoy.

You have described a connection to your grandmother, and her mother before her, through the making of wool hooked art. How have you brought this historical craft into the present day?

Wool hooking was known as rug hooking and at its beginning, it was a strictly utilitarian craft. Women would cut wool from whatever was on hand, such as old wool shirts or yarns from sweaters. Burlap feed bags were cut into the size of a run and stretched on a frame, and the wool was pulled with a hook through the openings in the burlap grid. Rugs were made to cover floors in rural areas long before they became machine made.

Because my grandmother enjoyed this art medium, and after I built a home on land that originally belonged to her on Prince Edward Island, Canada, I felt inspired to learn the art form that brought her such pleasure and sense of accomplishment. At present, wool hooked pieces are considered an expression of fiber art, and are shown in galleries and museums. My work has been accepted for gallery shows and juried art exhibitions, which has been a joy for me and a method of bringing this century old craft forward into the art world of today.

When did you start mixing wool hooking with painting, and how has this body of work changed or developed since then?

I purchased an art print by a well known artist from Prince Edward Island. It portrayed a red fox overlooking the sea from a cliff’s edge. I liked the print so much that I decided to make a pattern of the subject matter, and I hooked it with colorful yarns. I hung it beside the print of the painting on my porch on Prince Edward Island.

I looked at the print and hooked piece all summer long, and one day, I got the idea to combine the modalities after studying the effect of these two pieces in my mind. I heard my inner voice say, “Woolpaint”, and the words stayed with me. From then on I experimented with acrylic painting, collage, oil painting, alcohol ink and wool hooking to see how the effects of combining these modalities into Mixed Media art pieces that felt unique in my expression. My work continues to evolve.

Can you speak a bit about the inspiration for these three artworks in particular?

My inspiration is driven by my visionary experiences of an art piece. The beauty of the natural world’s landscape and animals represented in these pieces are an expression of my inspiration drawn from the world around me.

How does your creative process help you feel rooted to a sense of place, or belonging?

My work contains a continuous thread leading back to my grandmother and my ancestors in Canada and the United States. A sense of family informs my work.

What do you hope to communicate with your work?

Beauty. To paraphrase John Keats, in beauty is truth, truth is beauty. I don’t make angry or sad art. I try to celebrate the natural beauty of life.

Who are your biggest artistic influences?

My grandmother and the art and life of Georgia O’Keefe are by big influences. Many artists influence me, but I truly try to find my own way. I listen to that strong voice within, and although I admire many, I am compelled to express my individuality. I believe the artist within is like a fingerprint, unique and different from anyone else.

What have been your most fulfilling moments to date, as an artist?

When I am lost in the moment of painting or wool hooking I feel the most alive and filled with a sense of meaning. Having my art chosen for a show is a thrill just as making a sale makes my heart sing. But it is in the making where I feel most fulfilled.

What are you looking forward to for 2023?

I am working on a new collection I call The Grazers. It consists of portraits of animals, their individual faces call to me and make me smile.

Where can our readers see more WoolPaintArt?

You can find me at woolpaintart.com or on instagram @artful_woolpaint.

A Review by Aarron Sholar

Predator: a Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession by Ander Monson

Have you ever watched a movie, TV show, or even listened to a song so much that you could talk someone’s ear off about it? Well Ander Monson did, and instead of talking to us about it, he wrote a memoir. Predator: a Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession takes readers through the critically-acclaimed 1987 film Predator, seemingly frame-by-frame, as a sentiment of his love for the movie. But as the subtitle entails, this is not just a re-telling of the film he holds close, this memoir also tells the story of Monson’s troubled upbringing in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, the shooting of Arizona congresswoman Gabby Giffords, what it means to be American, and men. All these items, Monson shows us, are related to Predator.

The first thing Monson discusses other than Predator is men with guns. He writes that “I feel like I saw enough dudes with guns in the 1980s and 1990s for a lifetime” (4). This is where the writing of Monson begins to shine, and it makes this memoir so much more than just an obsession. But Monson makes the idea of obsession and connections the focal point very early on– “some cops get shot, I think of Predator. Some cops shoot kids. Guns in the grocery store, I think of Dutch, Schwarzenegger’s character” (5). The connections and obsession only escalates from here, and it all serves as a way for Monson to explore society through his own experiences.

Going into this book, I had never even seen the movie Predator. I knew it existed, and I knew it was a good movie, but I didn’t really know what the Predator looked like until I saw the cover of the book! However, my lack of prior knowledge did not deter at all from my reading, but rather it enhanced it! As stated previously, Monson brings readers through the entirety of Predator, complete with time stamps and all. Since readers are led through the whole film, those of us who have never seen it experience it in a very unique way, where we consider the men (of America), Monson included, the homoerotic undertones, the use of guns, and more of the movie.

But what is the point of Monson’s 146 viewings of Predator and his subsequent tangents (I say “tangents” with love)? Well, as much as I’d love to offer a profound meaning to the book, all I can say is that it’s about Predator. More specifically, it’s about the culture surrounding the movie itself, which Monson was actively a part of. For example, Monson writes that “I’m watching 1987 and I’m watching me in 1987. I mean, I watch it all the time. But every time that one line comes up it pushes the needle a little deeper” (61). The line in question is “slack-jawed faggots,” and Monson explains that “it was in the script– it wasn’t improvised. In fact, it was in a version of the script two years earlier” (61). Like many things, Predator, the movie, acts as a product of its time– it shows us what 1987 was like and the culture at the time. At other points, Monson explains how Predator can be watched as a Vietnam movie, or how many fans of it (men) discuss all the “manly” elements, such as guns and violence, but there are actually heavy homoerotic undertones from the very beginning.

Monson discusses how fans of Predator don’t get what he gets from the movie, how other white men his age don’t see the homoerotic undertones, that they stand strong in their reading (viewing?) of the movie as a classic 80s action film. This is what happens when we read Monson’s Predator memoir– we get out of it what sticks with us. Maybe you lean more into the impact of a partner dying of AIDS, such as Paul Monette’s, the author who wrote the novelization of Predator, did; maybe you also resonate with the intertwining of American white men, Predator, and 1987; maybe you focus on Monson’s ideas and notions on gun (control), also analyzed through the movie. For me, I read Predator: A Memoir, A Movie, An Obsession as a novel that allows Monson to discuss multiple topics he associated with the film itself– in a way, he is ranting at us, all while going on tangents about society and himself.

An Interview with Christian McPherson

Questions by Shallom Johnson, Art Editor

How long have you been drawing this series of Demented Doodles? How has the project changed or developed over time?

I am now 52 years old. I’ve been drawing since I was a kid. I did cartoons for my high school paper. I have been drawing my whole life but only in little spurts from year to year.

Demented Doodles began in the first week on the pandemic back in March of 2020. I started doing a drawing a day for over a year. Then it got a little spotty. But I have been fairly consistent with it, for the most part. For a while I felt obliged to do it. Now it’s just for me.

Where do you find inspiration for your visual art?

Other artists. Growing up, I had books by M. C. Escher, Van Gogh, Tomi Ungerer, Patrick Lane, Ralph Steadman, and a bunch of other artists and cartoonists. My father ran an art gallery so I was exposed to tons of art. Also consuming LSD, mushrooms and smoking dope – not that I engage in these activities, at least not in many years.

What draws you to pen and ink drawings as a medium?

I love it so much. There is something electric when I put the pen on the page. It’s like a current is flowing through me connecting me to the page. I don’t get the same thing with painting. Plus there is a kind of Zen elegance to just black and white. It’s clean. And I don’t pencil first, I just ink. If I make a mistake I start over.

Who are your biggest artistic influences?

The Far Side, Mad Magazine, Tomi Ungerer, Patrick Lane, Ralph Steadman, Rick Griffin, Gahan Wilson, and The New Yorker.

At first viewing, these two pieces present as abstract masses of line and shape. With a closer look, we see that interesting characters are packed tightly into almost every nook and cranny. Can you describe the process of building these drawings on the page? Where do your characters come from?

I started drawing this type of thing in high school but got way better at it when I was in university. I sometimes plan them with a theme. Sometimes I will start with a central character and then add and build around it. They grow organically. I often take long pauses and look at the space I am working with and “figure out” what should go there. I look at the shape of a line and think of what it could be – almost like looking at clouds. So I see it, then I draw it. They are fun to make but often very time consuming.

You’ve mentioned in the past that your principal fault is your sense of humor. How do you see that sense of humor manifest through your Demented Doodles?

I hope my drawings amuse people. For these type of drawings I also hope to amaze – “Oh, wait it’s actually an alien! And that’s a person with 3 heads.” And so on. Some of my drawings have been very political. Others, not so much.

You have a well-established body of work as a literary writer, with 12 published books including poetry, short stories, and fiction. How do your drawings relate to your writing practice?

Actually it’s only ten books and one anthology – ha. Well they don’t relate until this year. See the next question.

Any plans to blend these two worlds together in the future?

Glad you asked. So this year, 2023, my current publisher, At Bay Press, out of Winnipeg Manitoba, is going to be releasing my 11th book, 6th collection of poetry with the working title of, “Standing, Screaming Obscenities at the Sky.” I have given them close to 400 doodles to work with. I don’t know what exactly what it’s going to look like but I believe it’s going to be amazing and fun.

Where can our readers view more Demented Doodles?

This is my Facebook Page where you can find everything. I’m also on Instagram.

Anything else you’d like to mention that we haven’t asked about?

I am really into movies and have a blog for that.

Christian McPherson is a poet, novelist, and cartoonist. He lives in Ottawa Canada. He has written a bunch of books including, The Cube People, Saving Her, and My Life in Pictures. His latest book of poetry is, Walking on the Beaches of Temporal Candy.